By Mallory Holt

Wingert, Grebing, Brubaker & Juskie, LLP

It goes without saying that an attorney has an ethical obligation to be truthful to the court, but where is the line between persuasive argument and an ethical violation?

It goes without saying that an attorney has an ethical obligation to be truthful to the court, but where is the line between persuasive argument and an ethical violation?

“[A]n attorney’s ethical duty to advance the interests of [its] client is limited by an equally solemn duty to comply with the law and standards of professional conduct.” (Jerman v. Carlisle, McNellie, Rini, Kramer & Ulrich LPA (2010) 559 U.S. 573, 600 [alteration in original].) In many states, rules of professional conduct “impose outer bounds on an attorney’s pursuit of a client’s interests.” (Ibid.)

Every California attorney is required to employ “those means only as are consistent with truth, and never to seek to mislead the judge or any judicial officer by an artifice or false statement of fact or law.” (Cal. Bus. Prof. Code., § 6068, subd. (d).)

California Rules of Professional Conduct (“CRPC”), rule 3.3 governs an attorney’s ethical obligation of candor “in proceedings of a tribunal,* including ancillary proceeding such as a deposition conducted pursuant to a tribunal’s* authority.” (CRPC, rule 3.3, Comment [1].) Rule 3.3 requires in part that an attorney shall not “knowingly* make a false statement of fact or law to a tribunal* or fail to correct a false statement of material fact or law previously made to the tribunal* by the lawyer.” [1]

An attorney cannot avoid the prohibition on making false statements to the court by simply keeping quiet. “The concealment of material information within the attorney’s knowledge as effectively misleads a judge as does an overtly false statement.” (Griffis v. S. S. Kresge Co. (1984) 150 Cal.App.3d 491, 499.) “No distinction can therefore be drawn among concealment, half-truth, and false statement of fact.” (Grove v. State Bar of Cal. (1965) 63 Cal.2d 312, 315 [“The concealment of a request for a continuance misleads the judge as effectively as a false statement that there was no request.”].)

Even where the opposing party has overlooked an issue or the judge has not inquired further, attorneys have an obligation to fully disclose known information material to an issue before the court. “The duty of candor is not simply an obligation to answer honestly when asked a direct question by the trial court. It includes an affirmative duty to inform the court when a material statement of fact or law has become false or misleading in light of subsequent events.” (Levine v. Berschneider (2020) 56 Cal.App.5th 916, 921 [attorney improperly failed to disclose that after motion to enforce settlement was filed the settlement checks were received].)

The disclosure obligation applies even where the attorney believes the information at issue is objectionable or invalid. Such a belief “does not permit [the attorney] to act as final arbiter of its validity and withhold such information from the court.” (Glade v. Glade (1995) 38 Cal.App.4th 1441, 1457, fn. 16 [attorney’s failure to apprise trial court of prior stay order not justified by belief order was invalid].)

Counsel must also be cautious to avoid shaving down a square peg to force it in a round hole. The duty of candor is violated where information, although accurately quoted, is presented to the court in a piecemeal, misleading manner. (See Davis v. TWC Dealer Group, Inc. (2019) 41 Cal.App.5th 662, 667 [“We cannot help but observe the four ellipses in [appellant’s] quotation–and observe further [appellant’s] lack of candor, given how much the quotation misrepresents the Agreements here.”].)

Under CRPC rule 3.3, an attorney also shall not “fail to disclose to the tribunal* legal authority in the controlling jurisdiction known* to the lawyer to be directly adverse to the position of the client and not disclosed by opposing counsel . . .” (CRPC, rule 3.3(a)(1)-(2).)

While it may be tempting to avoid educating your opponent by omitting from briefing some authority beneficial to their cause, “[a]ttorneys are officers of the court and have an ethical obligation to advise the court of legal authority that is directly contrary to a claim being pressed.” (In re Reno (2012) 55 Cal.4th 428, 510.)

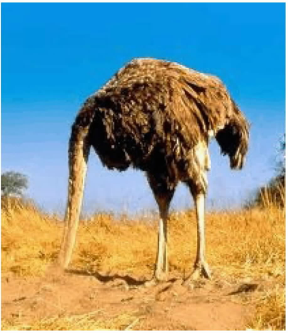

Counsel cannot avoid this disclosure obligation by unilaterally concluding relevant legal authority is distinguishable or outdated. (See Davis v. TWC Dealer Group, Inc. (2019) 41 Cal.App.5th 662, 677-678 [“hard to imagine a more obvious violation of Rule 3.3” where counsel claimed they did not advise the court of adverse authority because it was “different”]; Love v. State Dept. of Education (2018) 29 Cal.App.5th 980, 990 [failure to cite adverse seminal cases, which plaintiffs claim are “archaic and no longer applicable by modern standards,” “violates counsel’s duty to the court”].) As stated by the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals (in a published opinion complete with colored photographs to illustrate its analogy):

When there is apparently dispositive precedent, an appellant may urge its overruling or distinguishing or reserve a challenge to it for a petition for certiorari but may not simply ignore it . . . The ostrich is a noble animal, but not a proper model for an appellate advocate . . . The “ostrich-like tactic of pretending that potentially dispositive authority against a litigant’s contention does not exist is as unprofessional as it is pointless.” [Citations.]

(Gonzalez-Servin v. Ford Motor Co. (7th Cir. 2011) 662 F.3d 931, 934.)

Not sure whether authority is “directly adverse” for purposes of CRPC rule 3.3? Best practice, when in doubt, call it out! “[L]awyers should reveal cases and statutes of the controlling jurisdiction that the court needs to be aware of in order to intelligently rule on the matter. It is good ethics and good tactics to identify the adverse authorities, even though not directly adverse, and then argue why they are distinguishable or unsound. The court will appreciate the candor of the lawyer and will be more inclined to follow the lawyer’s argument.” (Batt v. City and County of San Francisco (2007) 155 Cal.App.4th 65, 82, fn. 9, disapproved on other grounds by McWilliams v. City of Long Beach (2013) 56 Cal.4th 613.)

[1] Terms followed by an asterisk are specifically defined within the Rules of Professional Conduct.