By Edward McIntyre

Macbeth introduced Michelle Gold to Sara and Duncan.

“Michelle’s a former student. She has an issue every trial lawyer — practice long enough — will likely face.”

Macbeth gestured to his guest to start.

“I’m in the middle of a trial. Yesterday I called an expert witness. He’s a computer scientist. Also a lawyer. Testified quite well. Did excellent on cross. Jury seemed impressed. Even Judge Howell liked him.”

Duncan nodded. “Good day for the home team.”

“Until we got back to my office. He sat down. Looked real smug. Said: ‘Well, we pulled that off.’ I froze.”

Macbeth intervened. “What happened?”

“He admitted all the tests he testified he’d done — never did them. Basically made up the results. Said if he’d done the work, he’s sure he’d have gotten those conclusions. But he was too busy. So he just wrote his report with findings he manufactured.”

Sara interrupted, “I’d have strangled him.”

“I almost did. When I told him he had to correct his report and testimony, he used a few expletives. Then left for the airport. We’re dark today. I talked with our managing partner. She said talk to you. So here I am.”

Sara replied, “This happened yesterday? California’s new Rules of Professional Conduct apply.”

“Which I haven’t had time to study. I’ve been too busy preparing for this trial.”

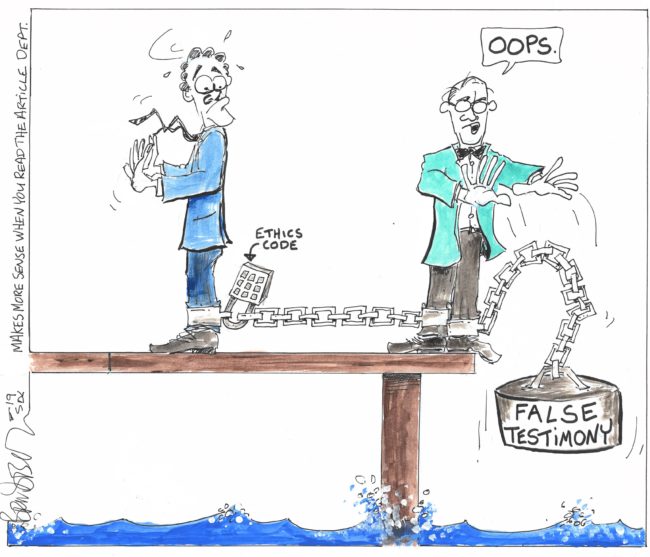

Macbeth opened his copy. “Rule 3.3 addresses candor to the court. Let’s start there. First, the rule prohibits a lawyer making a false statement of fact or law to a tribunal, or failing to correct a previous false statement. Not surprising. But not our facts.”

“Right, I didn’t make any false statement.”

“The rule does address our situation. If a lawyer, the client or a witness the lawyer called has provided material evidence, and the lawyer learns after the fact the evidence was false, the lawyer has to take ’reasonable remedial measures.’”

“What’s that mean?”

“The only guidance the rule itself gives is, ‘if necessary, disclosure to the tribunal,’ unless 6068(e)(1) and rule 1.6 — our client confidentiality obligation — prohibits disclosure.”

Sara interjected, “Since the client didn’t testify, I don’t see how 6068(e)(1) applies.”

Macbeth nodded. “I agree. The untruthful client presents a different range of issues. Let’s stay focused on this expert. I assume his testimony is material?”

“Critical to the case. Judge Howell even allowed his report into evidence as an exhibit. Over objection.”

“Does your client know — yet?”

“Not yet. I wanted some advice.”

“Well, rule 1.4 requires that you tell your client. This is certainly a significant development relating to the representation.”

“I agree. But I want to present a plan of action. Not just engage in a, ‘Houston, we have a problem,’ conversation.”

“Wise move. Let’s talk about solutions. First, the report that’s in evidence. What do you think?”

“How can I let it stand? I know it’s false. I think I have to ask the court to withdraw it.”

“I agree. Now, his testimony?”

“He won’t correct it. He’s gone back to Arizona.”

“What options does that leave you with?”

“Seems like the new rule won’t let me do nothing. So — tell the judge I have to withdraw his testimony? Instruct the jury to disregard it?” Michelle looked away. “My client will fire me. No, kill me.”

“You might first consider telling the court exactly what happened. Perhaps under oath. Ask for a mistrial. So you can find and present an honest expert. Your client shouldn’t suffer from this guy’s dishonesty.”

“If the court says no?”

“Once you’re honest with the court about the testimony, can you let it stand?”

“No —”

“So doesn’t that mean instructing the jury?”

“And if my client says no?”

“A comment to the rule says a lawyer also has to consider whether rule 1.16(a) might come into play and require withdrawal.”

“Sorry, you guys know these new rules a lot better than I do.”

Sara smiled. “Whether continued representation will result in a violation of the rules or State Bar Act.”

“Like this new candor rule.”

“Precisely.”

Macbeth signaled he had a question. “You talked to your managing partner?”

“Yes, she knows all the facts. Told me to get your advice.”

“Then rule 5.1 likely also comes into play. It addresses the duties of managerial and supervisory lawyers.”

“What’s that got to do with this mess?”

“If a lawyer with firm management, or direct supervisory responsibility learns another lawyer’s conduct violates a rule or State Bar Act provision, and does nothing when reasonable remedial action can avoid or mitigate the consequences, the manager or supervisor is also responsible for that lawyer’s ethical violation.”

“That’s a form of vicarious liability!”

“Fair way to put it. So you might suggest your managing partner give me a call.

We can talk this through.”

“Geez. What a cluster —”

Macbeth held up one hand. “You might also consider the inevitable finger pointing.”

“What?”

“Rules 1.1, competence, and 5.1 and 5.3, supervision, require us to supervise lawyers we employ — even those not in our firm — and non-lawyer contractors, among others. Be prepared for questions about how you supervised this expert and his work. Whether you consider him a lawyer or a computer geek.”

“So we’re talking malpractice?”

“Not directly. But the rules do help define a lawyer’s duty for purposes of a breach of fiduciary duty claim.”

“What about the guy who did all this?”

“Arizona has, with some modification, adopted the ABA Model Rules. Similar to California’s new rules. It has a rule 3.3 dealing with candor obligations.”

“Would that apply to an expert —testifying?”

“If he contends that he wasn’t ‘representing’ a client, there’s rule 8.4(c).

It says fraud, deceit, dishonesty all constitute professional misconduct. Manufacturing evidence likely fits.”

“I’ll say.” Michelle stood. “Thanks, Macbeth. Guys. I’d like to say I feel better. Perhaps a bit wiser.”

“Sometimes that’s the best we can hope for. We’re always here.”

Edward McIntyre is a professional responsibility lawyer and co-editor of San Diego Lawyer.

Editor’s note: Reference to “6068)e)(1)” is to Business and Professions Code section 6068, subdivision (e)(1); in BGJ Assoc. v. Wilson (2004) 113 Cal.App.4th 1217, 1227 the court reiterated that the Rules of Professional Conduct help define the duty component of the fiduciary duty a lawyer owes a client. See also Stanley v. Richmond (1995) 35 Cal.App.4th 1070, 1086-1087; Mirabito v. Liccardo (1992) 4 Cal.App.4th 41, 45.

No portion of this article is intended to constitute legal advice. Be sure to perform independent research and analysis. Any views expressed are those of the author only and not of the SDCBA or its Legal Ethics Committee.

This article was originally published in the Jan/Feb 2019 issue of San Diego Lawyer.