By Edward McIntyre

Macbeth sipped his Oban single malt, celebrating an appellate victory with Duncan and Sarah at Brennan’s Tavern. Fred Fox pulled an empty chair to their table — uninvited.

“Macbeth, I’ve got an idea I’ve gotta run past you —”

“Sorry, but we’re discussing a client matter —”

“Don’t worry. I won’t be long. This is killer.” Fox grabbed a passing waitress by the arm and ordered an orange mojito. Macbeth just closed his eyes.

“So, I’ve got this nephew. At college. We came up with this plan. I have him pay some of his fraternity brothers a few bucks. Say a hundred a piece. You know, beer and condom money. Or whatever kids do these days.”

Sarah, outside Fox’s line of sight, rolled her eyes.

“Anyhow, I pay my nephew another hundred for each kid he signs up. I’m out maybe two grand. Five tops.”

Duncan took the bait. “For what?”

“To be class-action plaintiffs, of course. You know, CLRA, UCL, FAL. Those kind of claims. Against these totally phony (making air quotes) ‘supplement’ products on the market. Kids wouldn’t even have to buy the stuff. Most of it’s garbage, anyhow. ‘Cure this. Make that bigger. Make it last forever.’ Garbage promises.”

Another eye roll from Sarah. Macbeth set down his Oban and took a deep breath.

“Doesn’t a consumer product class action have to allege that the plaintiff purchased a product, for example, relying on some representation, that it was false and the plaintiff suffered a resulting injury and that the plaintiff’s claims are typical of those of the class?”

Fox took a swig of orange mojito. “Yeah. So?”

“What business do you think you’ll take up after being a lawyer?”

“Macbeth, that’s almost insulting. Not a very funny joke.”

“Using a runner or capper is a misdemeanor that could lead to a year in jail and suspension or disbarment”

“Runner? Capper?”

“Yes, a person who acts as an agent for consideration for a lawyer to solicit or procure business. In the scheme you describe, your nephew.”

Sarah added, “The prohibition’s in the State Bar Act.”

“Rule 1-120,” Macbeth added, “prohibits assisting, soliciting or inducing a violation of the Rules of Professional Conduct or the State Bar Act.”

“Yes, but —”

“And the scheme, as you described it, also includes making false representations to the court and pursuing groundless claims. In the complaint. In any class-action motion. What about your client’s deposition? What does he say?”

Another swig of orange mojito. “Well, most cases don’t go that far. They see class action and run for the hills. Settle. Pay up. Before any class is certified.”

“And you keep the money?”

“Maybe give the kid another hundred. Haven’t thought about it that much.”

“Let me see if I understand.” Macbeth looked directly at Fox. “You plan on using a runner or capper to line up prepaid plaintiffs. They don’t even buy the product that is the subject of their claims that they did. They also claim they relied on advertising they never bothered to look at. And say that their claims are typical of a class of other consumers? And you’re doing this to try to force early settlements from these companies?”

“But I’ve collected some science articles and other stuff. They say the claims are garbage. That these supplements don’t do anything. So I’ve got probable cause, don’t I?”

“Do you have competing scientific studies that are favorable to the products?”

“Seen some. Haven’t looked at them. Probably paid for by the companies. You know how they are.”

“I don’t ‘know how they are.’ But I do know that for the lawsuit you describe you have no probable cause. Your prepaid plaintiff has no legitimate claim. You know it from the beginning. Not for himself. Not for a putative class.”

Final swig of mojito. “So I’ll have them buy the stuff. Hire my nephew. Part time. What then?”

“My view doesn’t change.”

Sarah nodded in agreement.

Duncan spoke up. “You’d be caught up in a host of Rules and State Bar Act violations. If a judge, opposing counsel — a competitor even — found out? Reported you to the State Bar? Boy, you’d need a miracle.”

Fox pushed his chair back and snatched up his messenger bag from the floor. “Gotta go.”

As Fox headed out the door, Macbeth lifted his glass ever so slightly. “You’re welcome, Fred. Anytime.”

Sarah and Duncan laughed and followed suit.

Editorial Note: Bus. & Prof. Code sections 6151-6154 prohibit using runners or cappers, criminalize it, void agreements and mandate fee divestiture. Rule 5-200 (A) & (B) and Bus. & Prof. Code section 6068(d) mandate candor to the court; section 6068(c) prohibits bringing actions except those that are “legal or just.” Rule 4-200 prohibits illegal and unconscionable fees, and Rule 3-110 requires supervision of subordinate lawyer and non-lawyer employees.

Edward McIntyre is an attorney at law and co-editor of San Diego Lawyer.

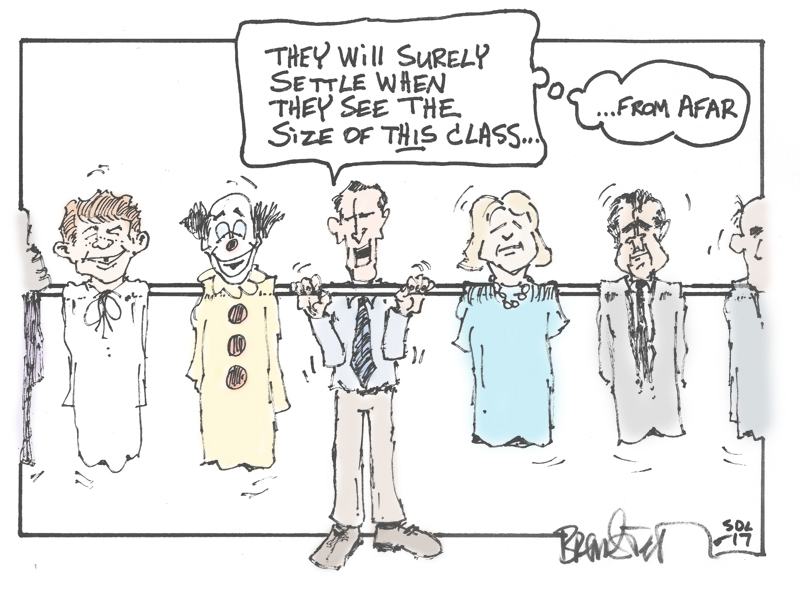

Cartoon by George Brewster Jr.

This article originally appeared in the

September/October 2017 issue Read More