By Edward McIntyre

Sara ushered two young women into Macbeth’s office.

“My friends, Samantha and Fiona, are opening their own firm.”

“Congratulations. A great adventure. Let’s move to the conference table.”

When all were seated, Macbeth asked, “How can we help?”

Fiona started. “We’ve been at large firms. Took things for granted. Now we have to be sure our firm does stuff right.”

Samantha joined. “There’s so much at the start. We’re grateful Sara suggested we meet you.”

“We’re happy to help. Let’s start at the beginning — new clients.”

Fiona laughed. “Best place to start.”

“You’re aware of the new rules?”

Both nodded.

“Let’s look at rule 1.7 — conflicts. It affects every new client. Each new matter.”

Macbeth opened his rules booklet and handed copies to Fiona and Samantha.

“Rule 1.7 (a) doesn’t change much. We can’t represent a client with interests directly adverse to another client without the informed written consent of each. Whether in the same or unrelated matters.”

Macbeth continued. “Now look at 1.7 (b). It requires informed written consent of each client if my responsibility to, or relationship with,” he started to tick the items off on separate fingers, “another client, a former client, a third person — or my own interests — will materially limit my representation of that client.”

Samantha looked up. “I’ve puzzled over that since I first read it.”

Macbeth set his booklet down. “We can talk about examples in a bit. First, how does a lawyer determine whether any such responsibility or relationship even exists? It starts with a practical problem.”

Fiona sighed. “A conflict check system. Something the firm always did. Our general counsel reviewed all new matters.”

Samantha shrugged. “We’re our general counsel now.”

Macbeth smiled. “Precisely. I can’t consider whether responsibility to someone, or a relationship, will materially limit representation of a new client — or a new matter for an existing client — until I identify the responsibilities and relationships each lawyer has.”

“Each lawyer?”

“Yes. If one lawyer has a conflict, it’s imputed to each firm lawyer.”

“Glad we’re only two. We can talk.”

“I suggest setting up your system from the beginning. Then, as you grow, it’ll be there for you.”

Sara added. “And save you from a world of hurt with disabling conflicts.”

Samantha opened a tablet and looked toward Macbeth. “ OK. Conflict check system.”

“Let’s start with the obvious. All current clients.”

Both nodded.

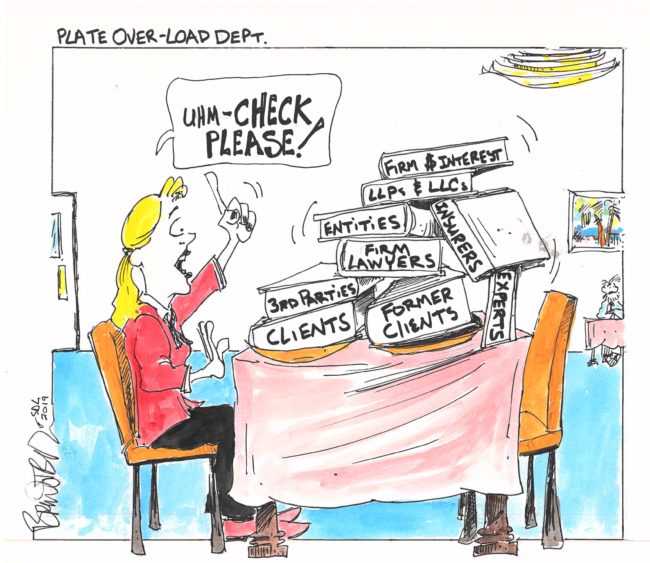

“Then, all clients you represented in the past. At your former firms. I suggest not only corporate, partnership and other entity names, but also fictitious business names. Also names of principal officers, directors and partners. Members of LLPs and LLCs. Then parent and subsidiary corporations — to determine if those relationships create a conflict.”

Fiona and Samantha both took notes.

“Be prepared to pick up corporate and partnership name changes. Entity clients sometimes merge. Get acquired. When you represent individuals, be aware of spouse or partner name changes after marriage or divorce. We also include names of insurers involved in any case.”

Fiona looked up. “Insurers?”

“Remember the tripartite relationship — if you represent an insured based on a contract of insurance, each is a client.”

“Right. Forgot. The firm didn’t do much of that.”

“You may not at your new firm. But I’d have a place for the information — if you do.”

Samantha spoke. “I can see an artificial intelligence-aided system really helping.”

Sara nodded. “ That’s what we have. Interactive. Fully automated.”

“But,” Macbeth held up a hand, “with hard-copy backup. Even with the cloud, one can’t be too careful.”

Samantha looked at her notes. “What else should we consider?”

“For each client, describe the representation’s subject matter. The responsible lawyer. Should be easy at the start. File number cross references.”

“OK.”

“I would also have a ‘connections’ section. Put in key witnesses, especially experts in litigation. Include anyone with a significant economic tie to your firm — other than clients.”

“For example?”

“Your accountant. Bank and banker. Insurance broker. Your landlord. Any other economic or personal relationship that might materially limit your ability to represent a client. Or take on a particular matter.”

“Wow!”

“Better to have the information. Then make the judgment call you don’t have a conflict.”

Samantha nodded. “I see that.”

“The unpleasant alternative is discovering later you had a conflict. Having to tell the client you may have to withdraw.”

“Other suggestions?”

“Three. Add persons who consult with you whom you decide not to represent. You may have learned confidential information creating a conflict. Or the person may claim you did.”

“Good point.”

“Make sure you have procedures to update your system. Do it religiously. Old data is almost as bad as having none.”

“I agree. Though it could be a pain.”

“It will be. But it pays off. Also, at our firm, we circulate an email among all staff — lawyers and non-lawyers — about each potential matter. Someone may pick up a possible conflict that the computer didn’t.”

“Should be easy with two of us.”

“But you’ll grow — I can tell. Set up the procedure now and it’ll be there.”

“More?”

“Don’t you think that’s enough heavy lifting for a start? We’re always here to help as you get going. You’ll do great.”

Fiona and Samantha looked a bit worn.

“Now would you join Sara and me for lunch?”

Their mood brightened.

Editorial Note:

Rule 1.7 does not expressly require a conflict check system; rule 5.1, Comment [1], however, identifies conflict checks as a critical element of client representation and firm management. Neither rule identifies what such a system should include. Macbeth intends his guidance to assist a conscientious lawyer trying to fulfill rule 1.7’s mandate to determine whether responsibilities to, or relationships with, the class of persons the rule identifies create material limitations requiring informed client written consent.

No portion of this article is intended to constitute legal advice. Be sure to perform independent research and analysis. Any views expressed are those of the author only and not of the SDCBA or its Legal Ethics Committee.

Edward McIntyre (edmcintyre@ethicsguru.law) is a professional responsibility lawyer and co-editor of San Diego Lawyer.

This article was originally published in the Mar/Apr 2019 issue of San Diego Lawyer.