By Edward McIntyre

Duncan knocked on Macbeth’s open door. “Uncle, got a minute?”

“Always. Come in.” A young man followed Duncan.

“Uncle, this is Duane. We’ve been having a … discussion. We’d like your thoughts.”

“Let’s ask Sarah to join us.”

With all four seated around the conference table, Macbeth asked, “What was the discussion about?”

Duncan started. “Approaches to discovery.”

“What’s the issue?”

Duane picked up. “I represent a client that’s party to an indemnification agreement. The more ‘triggering events’ covered by the agreement, the more money my client receives. The parties couldn’t agree on more than one triggering event. So, we filed a declaratory relief action. Have the court determine the number of events.”

“With you so far.”

“The defendant served a set of interrogatories. The first asks ‘How many events happened, for which payment is due?’”

“Sounds like a key question.”

“That’s the problem. I don’t want to answer it. Not yet.”

“Why?”

“The client’s documents suggest only one event. I need time to find more.”

“You propose?

“No more extensions to answer. Duncan and I were discussing — disagreeing about — a bunch of standard objections and then an answer that says: “The parties entered into an indemnification contract dated blah, blah, blah.’ Nothing more.”

“But no number?”

“No way.”

“Duncan thought that a bad idea?”

“How’d you know?”

“Well-trained. I suspect Sarah agrees.” She nodded and smiled.

“Shall we talk about your plan?”

“Yes, but …”

“The question is clear? Asks for a number? Number of events?”

“Yes —”

“The number of events is relevant?”

“It’s key.”

“If you answer as you propose?”

“They’ll object. Bunch of meet-and-confer. Likely months of it. Motion to compel. I’ll have to amend or supplement. Another answer. Perhaps buy more time. Meanwhile, my client has months to find more events that trigger payments. That’s the plan.”

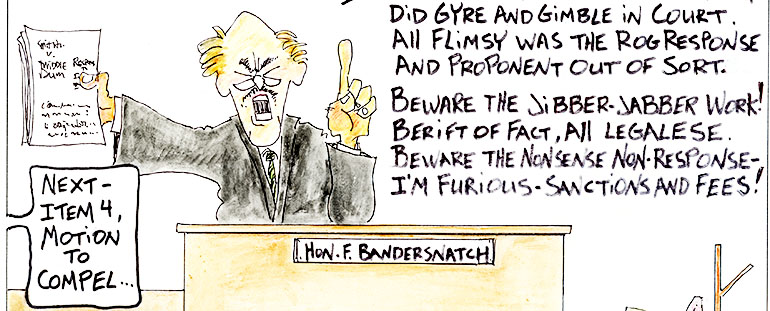

“Let’s consider some ethics rules that might apply. A new rule requires us not to use means with no substantial purpose other than delay or to cause needless expense. Another says we can’t unlawfully obstruct a party’s access to evidence or suppress evidence our client has a legal obligation to reveal. Yet another says, in representing a client, we can’t make a materially false statement to a third person. And there’s our obligation of candor to a tribunal. Make sure our client does the same.”

“What’s that got to do with the interrogatory answer?”

“The question calls for a number of events and it’s relevant?”

“Yeah, but —”

“The mumbo-jumbo answer about ‘the parties entered into a contract, etc.’ is just to buy time? Not for any other purpose?”

“Well —”

“Months of delay. Meeting-and-conferring. Motions to compel. All cause expense?”

On both sides —”

“Unnecessary expense — but for the mumbo-jumbo answer.”

“You’re saying it violates that new rule?”

“The other party has a legitimate right to a straight answer to the question, does it not?”

“You’re also saying I’m also interfering with their access

to evidence?”

“Think that’s a stretch?”

“No, but —”

“You’ll sign the answers and serve them on your opponent — a third person?”

“Yes.”

“Implying the answer accurately responds to the question — when you know it doesn’t?”

“But the statement is true.”

“Just not a true answer to the questions asked, no?”

“OK, but —”

“You’ll have a client representative verify the answer under oath?”

“Yeah.”

“Other rules prohibit assisting a client violate any law, rule or ruling of a tribunal or giving false evidence.”

“OK.”

“What about those documents you mentioned?”

“I’ll delay producing them — until I absolutely have to.”

“More delay? More obfuscation?”

“Well —”

“A motion to compel? Opposition? A court fight?”

“In this case? Yeah.”

“You’ll have to defend with a sworn declaration?”

“I see where you’re going.”

“Good. In addition to the ethics issues, think about your judge. He or she will see immediately you’re playing games.”

“I guess.”

“You’ve worked hard to build your reputation. Don’t damage it for this.”

“How do I answer?”

“Truthfully. If the answer is one event at this time, say it. Reserve the right, however, as discovery proceeds, to amend that answer if evidence supports more.”

“What do I tell my client? They won’t be happy.”

“Tell them the truth. You practice according to the Rules of Professional Conduct — because you have to. And because it’s good for the client, too, in the long run.”

Editorial Note: The Rules of Professional Conduct to which Macbeth referred are Rules 3.2 [delay of litigation]; 3.4 [fairness to opposing party and counsel]; 4.1 [truthfulness in statements to others]; 3.3 [candor toward the tribunal] 1.2.1 [advising or assisting the violation of law] as well as Business and Professions code section 6068, subdivision (d)

Edward McIntyre is a professional responsibility lawyer and co-editor of

San Diego Lawyer.

.