By David Seto

Today the United States and California are more diverse than ever. According to the U.S. Census, the share of the people born outside of the U.S. living in California has risen from 15 percent in 1980 to 27 percent today. There are nearly 11 million people in California born outside of the country. Most of these people are from Latin America or Asia and many are unfamiliar with our Common Law and our adversarial system. New immigrants tend to be younger workers or new students. However, as the immigrants age they will become more familiar and utilize the legal system for more services, not just immigration. It is therefore important for everyone to have what is called “cultural competency.”

In my own practice I represent many Asian immigrants. Having parents who were Asian immigrants themselves certainly helped bring some understanding of culture. For example, some Asian cultures believe that it is bad luck to talk about death. This makes it common for them to wait to do their estate plans until they are more advanced in age. In some cases this may be too late. This leads me instead to focus on more general legal education and outreach for clients who have other issues. There is less of a mental stigma for them to discuss it after resolving their other issues.

Although lawyers in this country have been representing people of other cultural backgrounds since revolutionary times, one of the leading articles on cross cultural lawyering, “The Five Habits” by Susan Bryant, was published in 2001.1

The five habits given by Bryant are:

1. Degrees of Separation and Connection

Identify differences and commonality between lawyer and client.

2. The Three Rings

Understand in each case the three parties: Client, adjudicator, and the lawyer, and what the adjudicator wants in the client versus how the client appears. For example, a jury may look at a tattooed client differently than a client wearing a suit that is covering tattoos.

3. Parallel Universes

Brainstorm alternate explanations for client behavior. For example, is the client late because he is irresponsible or is it because the client has no car and the bus is unreliable?

4. Pitfalls, Red Flags and Remedies

Identify problematic communications and their signs. The problematic communications to focus on are not using active listening for client understanding, using formulaic legal scripts explaining the legal process, formulaic introductory rituals such as intake interviews, or culturally specific information on the client’s problem. For example, during a personal injury intake, some risk adverse cultures may focus on any potential losses while other cultures may focus on the potential gains.

5. Camel’s Back

Differences in cultural understanding are like the straw that broke the camel’s back. One solution to this is creating situations with less bias and stereotypes and also conducting internal reflection and mental change on identifying and changing biases. For example, when stressed, the attorney may default to cultural biases — doing intakes under stress may not be the best option.

All of these habits are helpful framework, but they focus narrowly on the attorney client relationship and internal understanding. Cultural understanding is contextual and built not in a few billable hours here and there. To go beyond this, an external understanding is required of one’s own culture and other cultures.

First you need to understand your own culture. You belong to some culture. Examples of different cultural groups and identities are religion, nationality, race, gender, sexual identity, ethnicity, occupation, marital status, age, geographic region, urban, parent, military, or poor.

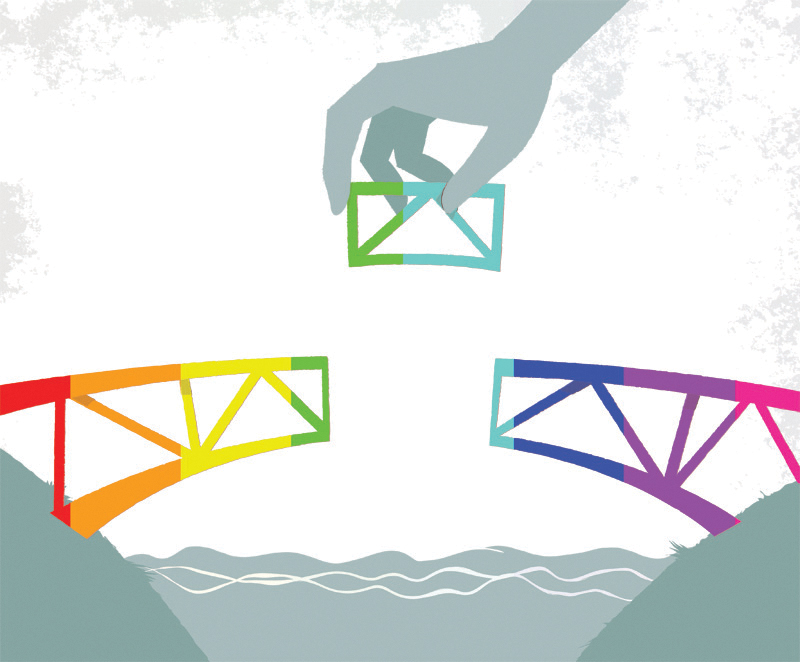

Finally you need to build relationships with other cultures. Some ways to do this are:

- Put yourself in situations where you will meet people in other cultures.

- Build friendships with people from other cultures either within your own groups or by joining or engaging with new groups such as people on recreational sports teams, others from different religions, your child’s PTA, etc.

Ask people questions about their own cultures, customs, and views. - Read about other people’s cultures and histories (from their point of view). Yes, Facebook counts.

- Listen to people’s stories.

- Risk making communication mistakes.

Consciously and frequently applying both internal cultural communications and external behavioral changes are the key to developing long-lasting and successful cross-cultural communication. Doing so can make the attorney client relationship easier and more fruitful for client and attorney.

David Seto (dtseto@gmail.com) is a partner with Ching & Seto APC.

1 Susan, Bryant. “The Five Habits: Building Cross-Cultural Competence in Lawyers” (2001). CUNY Academic Works.