By Edward McIntyre

Jessica and Brett are starting practice together. Today, they will discuss potential billing models with a senior attorney, Macbeth.

“Congratulations,” Macbeth said. “How can I help?”

Jessica started. “We come from firms that charged exclusively by the hour—”

“Actually,” Brett interrupted, “by six-tenths of the hour.”

“We’re exploring billing models that’ll make our services more affordable,” Jessica continued. “More flexible. For average people. Fewer can afford lawyers. But need them more.”

Macbeth smiled. “Commendable. What do you have in mind?”

Jessica continued, “We’re brainstorming several approaches.”

“For example?”

“We’ve discussed flat fees for specific tasks. Also guaranteed, not-to-exceed fees. And a monthly subscription plan — for unlimited services. A low hourly rate with contingency — for certain kinds of litigation. Smorgasbord, really.”

“Interesting. Shall we explore some ethical implications of a couple ideas?” Macbeth asked.

Brett spoke again, “We’re wide-open to suggestion. Before plunging ahead.”

“Let’s start with the flat fee.”

Jessica explained, “It gives a client certainty. Right from the start.”

“I agree. Ethically, unless it’s a true retainer — what you describe isn’t — you’ll have to put the funds in your client trust account. Unless your client agrees in writing, after informed consent, that you don’t.”

“Informed consent?” Brett asked.

“Yes. You tell the client in writing that they can require you to put the funds in your trust account and that the client gets refunded any unearned fees. Then the client consents in writing.”

“Who’d do that?” Jessica questioned.

“Precisely. Likely few. So most flat fees will go into your trust account.”

“What’s ‘unearned’ mean?”

“Assume you accept a flat fee to draft a contract. Then the client fires you before you’re done. Some of that fee’s unearned. Correct?” They nodded, tentatively. “But how much?” Macbeth continued.

Jessica asked, “How do we deal with that?”

“Consider having benchmarks in your engagement agreement. At least for all but the simplest task. You and the client agree at the outset that portions of the fee are earned as you complete specific steps.”

Sarah interrupted, “Of course, then you have to take those earned funds out of your trust account. They’re now your funds.”

Macbeth went on, “You mentioned a subscription plan. I’m intrigued. Clients make periodic payments? Get unlimited services? How do you anticipate that working?”

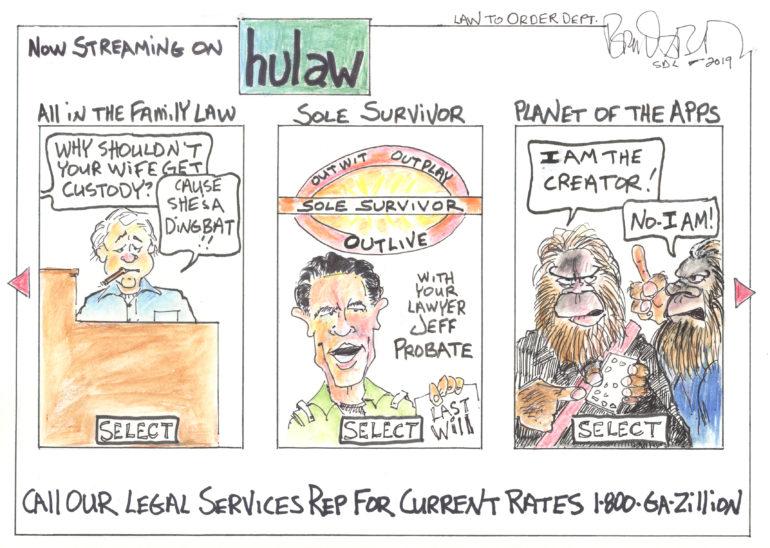

“People are used to subscriptions. For all kinds of things — Netflix®, Amazon Prime®. They budget, pay monthly fees and get access to services they want. We thought about offering something similar. Clients pay a small monthly fee. Get unlimited phone calls on legal issues. Or emails. Or document review.”

“For every discipline?” Macbeth raised his eyebrows.

Jessica laughed. “No way. Only where we feel competent —”

Brett completed the thought. “Like family law, business formation, contracts for Jess. I’d take employment, simple IP, pre-litigation issues.”

Macbeth asked, “Could you handle possible high volume? I see competence and diligence issues.”

“We’d expect it might be high — initially. Then drop off. We have three talented paralegals whom we’d use to help screen and direct the traffic,” Brett explained.

Jessica added, “We’d limit document review to a set number of pages. After that, a surcharge. Limit phone calls to a specific duration. We’d have to craft some parameters.”

“From a professional responsibility viewpoint, consider the scope of services you’ll provide. Make it clear in your agreement. Because you limit what you’ll do, you have to state it carefully. The client has to give informed consent.”

Brett asked, “What about a client who abuses the subscription? You know. Calls 10 times a day with nonsense stuff?”

“Fine question. A client can always fire the lawyer. We, on the other hand, are bound by Rule 1.16.”

Jessica and Brett turned to the rule in the small blue book Macbeth gives visitors.

“You could consider language in your agreement that allows you to terminate the representation unless bad behavior changes … but then you’d have to warn the client. Wait and see.” Jessica nodded, “I see the problem.”

“You also have Rule 1.16(b)(4). If the client’s conduct makes it unreasonably difficult for you to carry out the representation —”

“Ten calls. Every day. With nonsense!”

“But remember, even if you ethically terminate the representation, you still have to take steps to avoid reasonably foreseeable prejudice to the client.”

“OK,” the two agreed.

“At a minimum, give notice. Allow the client time to get another lawyer,” Macbeth paused, “but I don’t mean to discourage you.”

Brett laughed. “We’re not discouraged.”

“Don’t be. You’ve got imaginative ideas. Access to justice is a critical issue for so many. It’s becoming more acute. I applaud your efforts to develop creative approaches. We’re always here to help.”

Edward McIntyre is a professional responsibility lawyer and co-editor of San Diego Lawyer.

Editorial Note: Some Rules of Professional Conduct Macbeth addressed, without specific mention, include: Rule 1.2 (b) (limited scope of representation; Rules 1.5 and 1.15 (fees and client funds); Rules 1.1 and 1.3 (competence and diligence); and Rule 1.16 (termination of representation).

Excellent piece.