By Shannon Bales

For many, the first use of trial presentation technology is trial by fire: they are thrown into a less-than-ideal situation. After all, everybody gets their start somewhere. The current tech reality in the courtroom is that lawyers seem to forget that going to trial is the most visible and high-stakes aspect of the work they do—and if the media are involved, their audience will go far beyond their clients and colleagues. Many lawyers simply do not have the commitment to technology used in the courtroom that they should have and it shows in the way they present their case and can create a negative effect on

Trial tech can be a great equalizer in the courtroom, such that even solo practitioners can match the professionalism and high-quality presentations of a mega firm in their ability to create and present electronic evidence at trial. Trial presentation is neither impossible nor overly technically difficult, but there are bars to entry—namely, a minimum technical skillset, the right equipment, and the basic knowledge necessary to create electronic exhibits in PowerPoint or trial presentation software like TrialDirector, Sanction, or OnCue. Too often, people wanting to use courtroom technology are thrown into situations that are beyond their ability.

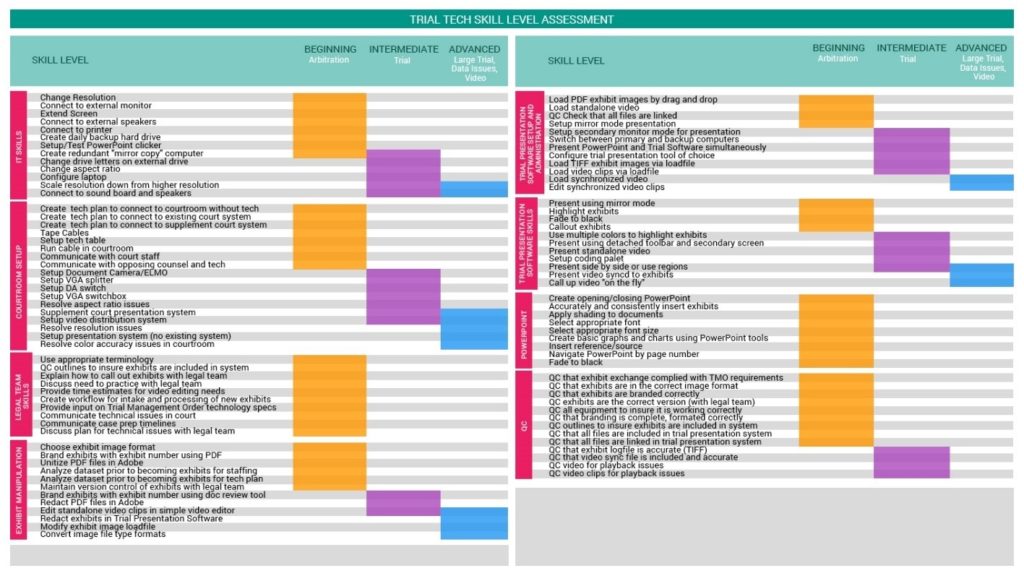

It is important that attorneys have the requisite skills and experience need to be correctly applied to the case at hand, a concept that should be entirely familiar to lawyers in the partner system. The most senior heavy-hitters are brought in for the biggest and most difficult cases, while new associates cut their teeth on smaller or less difficult legal matters. Staffing for the technical aspects of your case is really no different. For larger and technically difficult cases, experience matters and you’ll want to use the services of an experienced trial technician, while smaller cases might be the right opportunity to develop someone on the legal team into a trial technician.

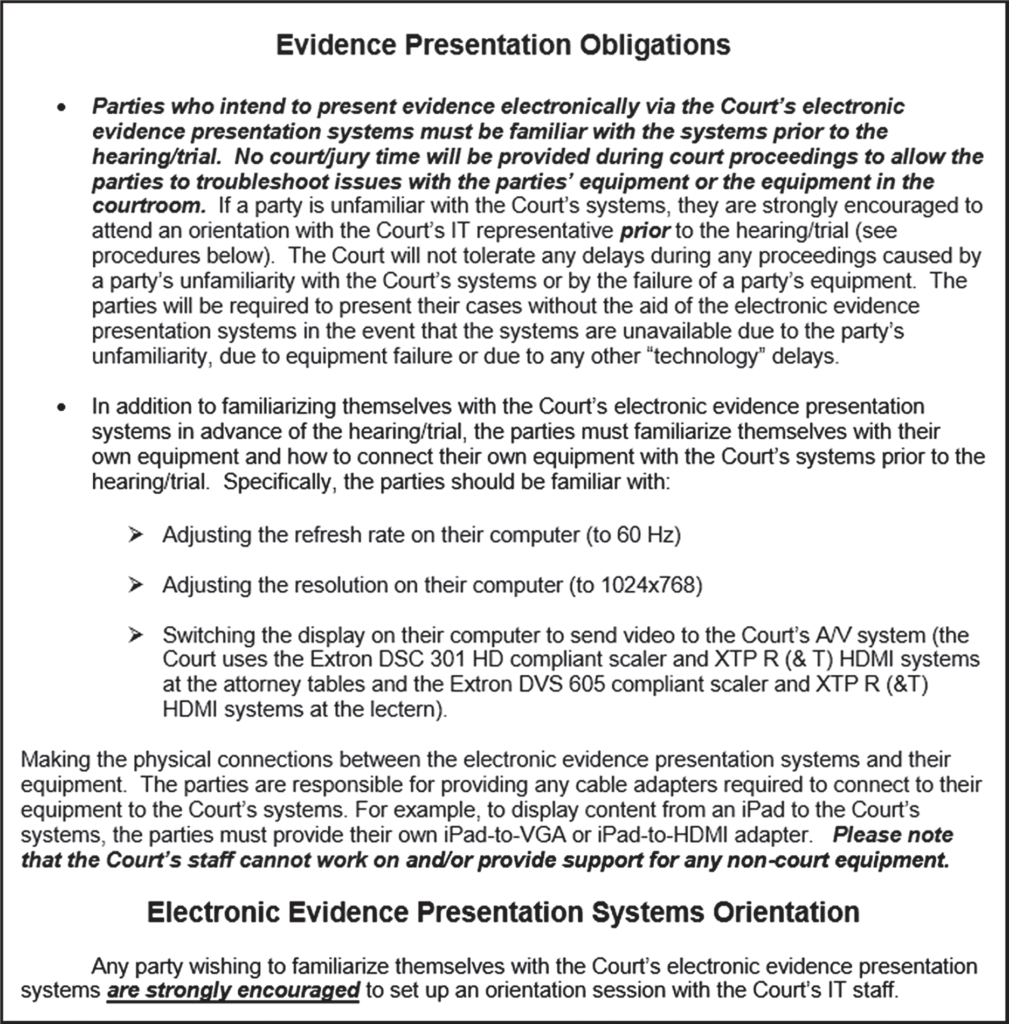

Courts are now issuing rules establishing minimum technical standards for legal teams when they use high-tech equipment at trial. The required skill level is referred to as “Evidence Presentation Obligations,” and these obligations are mandated by many courts, along with the mandated use of technology. Legal teams are in a real bind if they don’t know how to use their own and/or the court’s equipment. Below are a few excerpts from a list of evidence presentation obligations that some federal courts now use:

- “No court time will be provided during court proceedings to allow the parties to troubleshoot issues.”

- “The Court will not tolerate any delays during any proceedings caused by a party’s unfamiliarity with the Court’s system or by the failure of a party’s equipment.”

- “In addition to familiarizing themselves with the Court’s electronic evidence presentation system in advance of the hearing/trial, the parties must familiarize themselves with their own equipment and how to connect their own equipment with the Court’s system prior to the hearing/trial.”

How ridiculous is this: “the parties must familiarize themselves with their own equipment and how to connect their own equipment with the Court’s system prior to the hearing/trial.” How many people came to court without knowing how to use their own equipment? Apparently enough to where courts had to make a rule.

Truth be told, if lawyers simply did the following three preparation steps below their courtroom technology experience would run much smoother for all involved with less technical failures (by one courtroom IT account more than 60% of technical issues experienced in Federal Court are completely avoidable with just minimal planning and testing – who isn’t doing the bare minimum?).

- Be familiar enough with your own laptop that you know how to connect to a video source, configure the sound and video and put the computer into “extended screen”. Basic technical competence is quickly becoming the norm. I’ve included some “evidence presentation obligations” some Federal Courts are requiring below. Take a look at their terse wording and let me know if you think if courts are tired of watching lawyers bumble and stumble thru their presentations.

- Test your laptop/tablet in advance in the courtroom you will be using. Can you connect your laptop to the courts system? Do you need to bring speakers for audio or video? What resolution do the courtroom displays use when working with your own laptop?

- Have the appropriate level of support necessary for the technical needs of your case. Putting up a couple exhibits on screen is no big deal if you can do 1 and 2 above – but coercing your paralegal or first year associate to become a trial tech overnight for a technically difficult case is unfair to all involved.

If the basic concepts and terminology above are beyond your skillset you need to either hire a professional trial tech consultant (there are many in this area) or take a class to up your skills. Casual tech users often over simplify or lack the basic IT skills they need to perform a relatively simple “plug and play” courtroom setup. How can a team that doesn’t understand its own equipment, doesn’t take basic QC steps for its own technology, or doesn’t know how to comply with simple exhibit exchange standards be working efficiently and competently itself? Embarrassing problems and technical glitches occur when people are in over their head.

Using courtroom technology is full of potential gotcha moments. If you can get your start on a small trial or arbitration—with a limited set of documents to unitize, redact, and brand in Adobe Acrobat PDF format; load into your trial presentation tool of choice; and present in court—you will have the perfect opportunity get started. Be careful not to go too far outside of your skillset and comfort zone, as you might be asking for trouble. (take a look at some of the basic skills in the chart below).

Most issues that occur in a presentation are not due to a sudden technical calamity. They can be anticipated. Why? Because most issues are usually due to bad planning and poor preparation by the legal team. Poor choices made in planning almost always result in an embarrassing courtroom failure. It’s mortifying to explain yourself to decision-makers (especially when they are a client) for a failure that could have been avoided with an advance visit to the courtroom or extra money for appropriate equipment.

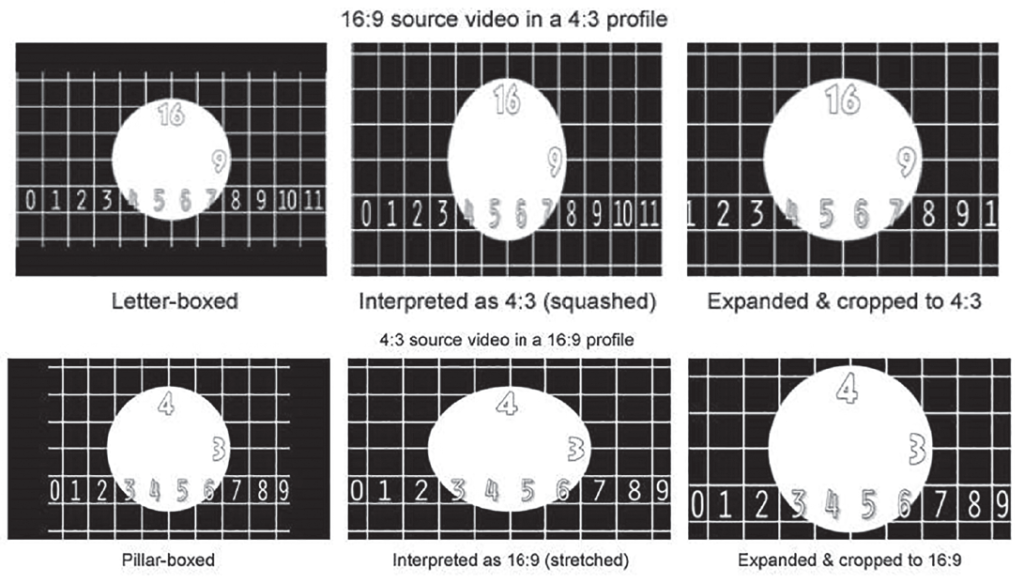

Such failures slow the adoption of courtroom technology through bad prior experiences of users (i.e., the judge and lawyers). It is completely disheartening to come to a courtroom and be told by the clerk that the judge does not like technology due to the multiple bad tech experiences in trials. Too often, the first visit to the courtroom is on the first day of trial for attorneys because they simply don’t take their technical obligations seriously. This lapse alone causes irreparable harm. How will the legal team know what resolution to create their presentation in? Or what size and scale? Will the aspect ratio of the courtroom change the presentation to make it unreadable to viewers? The graphic below shows the effect of aspect ratio when it is done incorrectly (for example, a PowerPoint created on your 16:9 work computer being displayed on a 4:3 court monitor). Note how the image can be stretch or squashed – I see it all the time.

Remember: technology is allowed into the courtroom to help speed things along and make the trial process more efficient. Courtroom technical problems have a profoundly negative effect on decision-makers like the judge and jury. It’s a bit like baseball—three strikes and you’re out, because from the court’s perspective, you’re messing with the number-one goal of courtroom technology: the swift and efficient administration of justice. Maybe MMA fighting is the better analogy: you may get pummeled and embarrassed and lose in seconds if you’re incompetent right out of the gate. But you don’t have to take my word for it.

In a recent Cornell Law Review article on “What Juries Really Think: Practical Guidance for Trial Lawyers” by Judge Any St. Eve and Gretchen Scavo (Winston and Strawn Partner) they explored the attitudes towards technology of 500 jurors from 2011 to 2017 in Chicago Federal Court on what they thought of the lawyers they saw at trial, in other words what they liked — and what they didn’t. This study supports that idea that technology preparation and practice are an invaluable part of trial prep. Many teams simply ignore the technological needs of their case or underestimate them causing problems with Juror perception of their professionalism and ability to present their case.

Some findings from the study on what jurors liked the most:

- Organization/Preparation and Efficiency

- Delivery or Style of Presentation

- Good Behavior Toward Opposing Counsel, Witnesses and/or Jury

Conversely it was the same areas that the survey respondents suggested attorneys could do better in.

- Organization/Preparation and Efficiency

- Present More and/or Better Evidence

- Improve Presentation Delivery or Style

Selected Juror Comments from the Survey:

- did not like “technology problems, power plugs, evidence tapes” and would like to see attorneys “make sure [to] have technology ready”

- “would have liked to see [the attorneys] operate computers better”

- “learn how to use equipment in advance”

- liked “the photos being shown on the TV in front of me” and “witnesses being able to use . . . computer screens”

- wished attorneys would “learn how to use the computer” and the “computer cut off sentences”

- “why couldn’t the defense use laptops to present evidence like the prosecutors?”

- would have liked to see the “defense have their things on [a computer] better to view”

- liked the “defense[’s] use of the technical equipment”

- liked that attorneys “used [a] TV monitor to see pic[tures] easily”

- liked that attorneys “put visuals on the screen”

- “the summary visuals were helpful”

The judge (nor anyone else) doesn’t want to watch you bumble and stumble through technical problems because you don’t have the skills necessary to run your computer or software, didn’t bother to prepare, or can’t connect your laptop to the presentation system. I’ll say it again: much of this drama can be avoided if you test and prepare your equipment in advance. Testing not only helps you lower the risk of technical glitches, but also gives you an idea as to what resolutions will work in the courtroom and to which shape (i.e., 4:3 or 16:9) you should tailor your presentations. The takeaway here is that you want to test your equipment (and self-assess your ability) in advance. Practice your opening, closing and witness examination with your technology as you envision it being used in the courtroom.

Quality, stability, and risk reduction come from taking the appropriate steps in building a solid foundation for a presentation—and not merely learning how to push a few buttons to put a trial exhibit image onscreen. No matter which trial presentation tool you use or even if it is just PowerPoint or Acrobat, they all share a common need for planning, preparation, quality control, and a multitude of companion skills that are not taught in the training for your tool of choice. While trial presentation can be simple, it can also be deceptively difficult if you paint yourself into a corner by choosing the wrong image format, using an overly difficult exhibit branding scheme, don’t test the equipment in advance, or lack the skills necessary to do the job.

Your credibility, technical competence, and conduct make the difference between being viewed as capable or incompetent when a legitimate technical issue occurs in trial. You may get more latitude if you have repeatedly demonstrated to the court that you take your commitment to technology seriously if you have tested your equipment and the courtroom system, have backups in place, and displayed technical competence over someone who has not. When difficulties occur, it is often an all-or-nothing proposition: either you did it right and the exhibits are all loaded and displaying correctly, or you didn’t and they won’t. This is why quality control (QC) is so important. Everything must be checked (repeatedly) because there is no second chance. The court is not going to reschedule the opening or the closing, or have a witness come back, on account of missing data or your constant computer crashes. Openings that were prepared weeks in advance sometimes go unused because the team’s trial technology does not work the first time—and this means the team has to wing it. Wing it for opening? Time spent prepping and testing equipment, exhibits, and presentations is well spent, not wasted.

There are great working benefits to legal teams of having your technical house in order (e.g., organization, technical compliance, war room performance). Simply being able to quickly create, share, and print an exhibit is a tremendous benefit (and possibly a competitive edge) to a legal team in terms of being able to prepare and present. Going into trial, teams should have a very solid understanding of what their technical responsibilities and burdens will be when they agree to the technical specifications for an exhibit exchange. Lawyers should consult with team members who are familiar with the data as it currently stands and those who will be working with it at trial so the best decisions can be made in working with the teams’ data. You would be surprised at how often the plaintiff and defendant make combined decisions that are counter to their own self-interest and create tremendous burdens on their respective support staff to comply with that are completely unnecessary. A final point: there is a vibrant in-house and consultant community that can assist and should be consulted when preparing for and being at trial.

We are heading toward a new expectation for firms and lawyers in that they have made at least the minimal commitment of having the technical skills and ability required for trial presentation. Firms should decide on the minimal level of service and support they will offer at every trial, and whether they will absorb or pass through some of those costs. Lawyers who are an “army of one” must understand that possessing the minimum of technical competencies is on their shoulders and they must take steps to ensure they comply. For those worried about “plugging in” to a court system, much of the worry and doubt can be removed simply by testing in advance. The choice is clear: technology is coming and lawyers will need to adopt, hire or get out of the way.

Shannon Bales is Managing Director for Forensic & Litigation Consulting