By Edward McIntyre, Cartoon by George Brewster Jr.

Duncan hovered at Macbeth’s door, another man in tow. “Can we disturb you, Uncle? My friend, Smedley.”

“You have. But come in and take a seat. Shall we invite Sara to join us?”

When everyone was comfortable, Macbeth turned to Duncan: “Did you and Mr. Smedley have a question for us?”

Duncan nodded toward Smedley. He started.

“I have an office here. Also one in Phoenix. Got a couple of difficult clients at the moment. Don’t like questions they’re asking. Stuff they’re saying. I think it’d be good if I used my Phoenix office to talk to them. Record the calls.”

“Because Arizona is a single-party consent state?”

“Precisely. California requires both parties to agree.”

“Your concern is ethics?”

“Among other things, but yes.”

“As a California lawyer, you’re still governed by our Rules of Professional Conduct. And our State Bar Act.”

“OK.”

“Let’s look at this based on the new rules that go into effect November 1.”

“Makes sense to me.”

“Rule 8.4, subdivision (c) says it is professional misconduct to engage in conduct involving dishonesty or deceit or intentional misrepresentation.”

“OK, but —”

“And rule 4.1 prohibits making a material false statement to a third person when representing a client.”

“But —”

“Then, rule 1.4 requires a lawyer to keep a client reasonably informed about significant developments relating to the representation.”

“So —”

“And, of course, section 6068 (e)(1) and rule 1.6 still require us to protect client confidences and secrets at every peril to ourselves. That did not change.”

“Yeah, but —”

“Finally, we have our duty of loyalty. Hallmark of our profession. Key to our relationship with a client.”

Macbeth looked at all three young lawyers. “Against this backdrop, how would you analyze surreptitiously recording a client’s call?”

Sara spoke first. “When the ABA re-examined an older opinion in 2001, its committee on ethics and professional responsibility was divided on whether a lawyer could record a client call without a client’s knowledge. But the committee agreed it was inadvisable to do it.”

Macbeth nodded. “State Bar opinions across the country are split on nonconsensual taping, even where it’s legal. They don’t give us much guidance. So let’s look at it with fresh eyes.”

Duncan spoke. “Can’t hurt.”

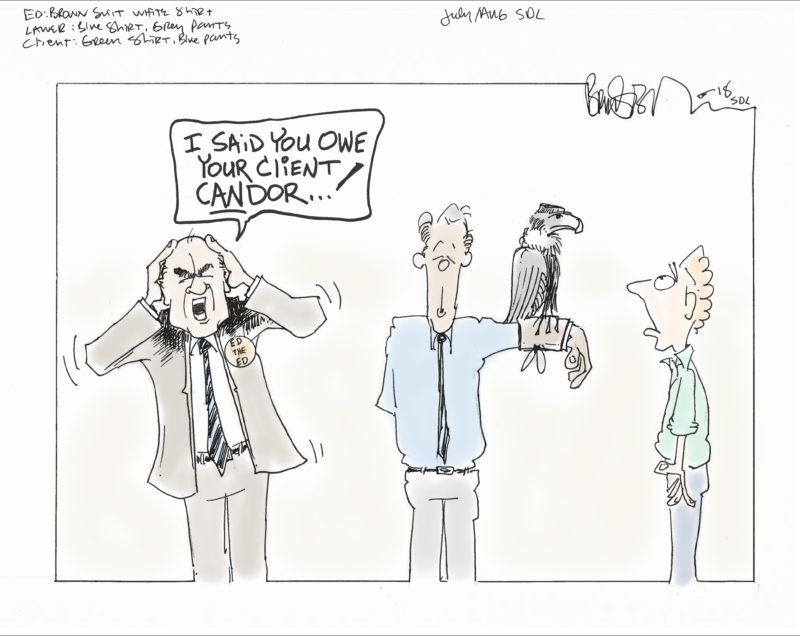

Macbeth picked up the thread. “Is surreptitious taping a client’s call deceitful conduct, under rule 8.4(c), at least implicitly? And if rule 4.1 prohibits a lawyer from making false statements to total strangers, do we not owe a special duty of genuine candor to clients?”

Smedley spoke. “Lawyers take notes of calls with clients all the time. Or dictate memoranda. What’s the difference?”

Duncan shrugged and nodded.

Macbeth spoke. “Good question. When a lawyer takes notes, don’t we have — for the most part — the lawyer’s impressions of what the client said? Even when the lawyer puts down a quote or two, we don’t have a recording that captures the ‘client’s exact words, no matter how ill-considered, slanderous or profane’ as the ABA opinion expressed it.”

Smedley spoke. “True but —”

“Then don’t we have to consider the embarrassment and harm to the client if the recording falls into unfriendly hands. By operation of law. Or inadvertent disclosure. Or even illegally. Don’t we agree that the recording would be much more damaging to the client than just the lawyer’s notes?”

Smedley again. “Well sure, but —”

“If we have the duty to preserve our client’s confidences and secrets at every peril to ourselves, don’t we put that obligation at risk by making secret recordings of client conversations? What countervailing good do we serve by doing it?”

Smedley spoke. “As I said, I don’t like stuff these clients are saying. Questions they’re asking. Frankly, I need to protect myself.”

“Aren’t there better ways to protect yourself, as you put it? If the relationship is deteriorating to the point you think you need to tape their calls, maybe you should disengage.”

Smedley just shrugged.

“Let’s also consider the duty to keep a client reasonably informed about significant developments. Do any of us think that secretly recording a phone call is not significant? It’s certainly a development in the representation. I think rule 1.4 also has a role to play in this discussion.”

Smedley looked down at his hands.

“What about your duty of loyalty to these clients? How would they react if they learned of the secret recording?”

“Pissed.”

Macbeth nodded in agreement. “Rightly so.”

Smedley looked up. “So you think it’s wrong?”

“Given the rules and principles we considered, I think it’s unethical. Could a State Bar prosecutor make out a discipline case against you to a clear and convincing standard? Hard to say. Could one of your clients assert a breach of fiduciary duty claim against you, using the rules to define your duty to the client? More likely — in my view. Is there a single black-letter rule I can point to that says it’s verboten? As we saw, no. Yet I conclude it’s unethical for a California lawyer to do it — at least after November 1.”

Sara added: “As the ABA said in 2001, although it couldn’t reach a conclusion about the ethics of secretly recording a client’s call, the committee agreed it was inadvisable.”

Editor’s note: The ABA opinion to which Sara referred is Formal Opinion 01-422 (June 24, 2001), which cites some of the State and County Bar opinions on the subject. New and revised Rules of Professional Conduct are effective November 1, 2018, in California.

Edward McIntyre is an attorney at law and co-editor of San Diego Lawyer.

No portion of this article is intended to constitute legal advice. Be sure to perform independent research and analysis. Any views expressed are those of the author only and not of the SDCBA or its Legal Ethics Committee.

This article originally appeared in the July/August 2018 issue of San Diego Lawyer.